How Lenny Bruce’s letters came to live at Brandeis

By: James Sullivan, Boston Globe

For the most part, the fading photos of the little family — the husband, the wife, their daughter — look like snapshots of any other contented American family of the 1950s. Except maybe for the one in which the father is flipping the bird.

For the most part, the fading photos of the little family — the husband, the wife, their daughter — look like snapshots of any other contented American family of the 1950s. Except maybe for the one in which the father is flipping the bird.

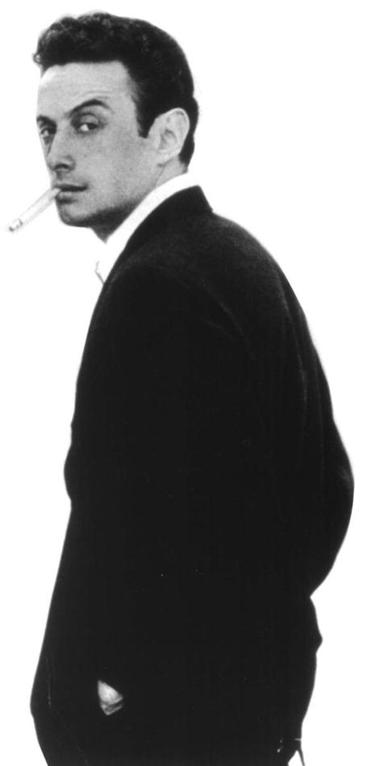

When Kitty Bruce, the daughter of the late, confrontational comedian Lenny Bruce, pulled her father’s memorabilia down from her attic a few years ago, she saw deeper into his unique mind than she had for years.

“I started to see that he was born broken,’’ says Kitty, 59. “You could tell he was constantly reaching for approval, looking for that ‘attaboy.’ ’’

Almost 50 years after Lenny Bruce’s death, the very private daughter of comedy’s patron saint of free speech has placed his papers — six boxes consisting of 10 linear feet of material containing newspaper clippings, personal letters, photo albums, reel-to-reel tapes, concert posters, and more — in the Special Collections department at Brandeis University in Waltham. The acquisition, announced last year and due to be unveiled at an exhibition planned for late 2016, puts the work of the “sick”-humored comic (as Time magazine once infamously labeled him) in the permanent company of some august, and in many ways fitting, classmates.

Among others, the Brandeis library archives are home to collections pertaining to Sacco and Vanzetti, the Italian immigrant anarchists executed in 1927 whose guilt is still debated today; Joseph Heller, whose absurdist 1961 novel, “Catch-22,” helped define the anti-Vietnam War spirit of the era; and Louis Brandeis himself, the first Jewish Supreme Court justice, whose legacy rests on his rigorous defense of freedom of speech.

The Brandeis collection of Bruce’s personal papers will give future scholars of comedy, popular culture, and the First Amendment an unprecedented glimpse into the inner workings of a comedian still considered the archetype of the art form’s audacity.

One black-and-white photograph in the collection is an 8-by-10 enlargement of a candid shot of Bruce holding a phone to his ear. It’s clearly marked on the back: “Photo by Phil Spector.”

Kitty Bruce says that some of the ephemera she delivered to Brandeis was stored for a time in the home of the actor Robert Blake — like Spector, another of her father’s old pals.

“All of my father’s friends have been blamed for shooting people,” she said wryly, speaking on the phone from her home in Pennsylvania. “I don’t know what that scene is all about.”

Lenny just shot his mouth off. Bruce, the author of the autobiography “How to Talk Dirty and Influence People,” got his start on such early television staples as “The Steve Allen Show” before becoming a cause celebre in the activist 1960s. Arch routines such as “Religions, Inc.” and “How to Relax Your Colored Friends at Parties” addressed the country’s absurdities and inequalities head-on, and often landed the comedian in the sights of censors.

His propensity for speaking the truth as he saw it — about hypocritical attitudes toward sex and language, race relations, and organized religion — got him into near-constant trouble with the law before the liberation of the ’60s took hold, leading to multiple arrests and, ultimately, the landmark free-speech trial in New York that wore him down to his drug-related death at 40.

He was sufficiently iconic in his day to earn a place of prominence in the gallery on the cover of the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” album, a year after his death. In 2003, then-New York Governor George Pataki granted Bruce the first posthumous pardon in the state’s history for his conviction in that 1964 obscenity trial.

For American Studies professor Steve Whitfield, the Lenny Bruce papers are a natural fit at Brandeis. He points to “Brandeis’s uniqueness as a Jewish-sponsored, nonsectarian university that has historically, among its faculty and student body, taken a stance of dissidence or insurgency toward the injustices of society, which Lenny Bruce satirized.”

The papers found their way to Brandeis through a series of serendipities. Whitfield served a decade ago on a committee at the University of Paris as a doctoral candidate named Steve Krief defended his dissertation, “Humor and Representation in Lenny Bruce’s Work.”

Krief, who is now on staff at L’Arche, France’s oldest Jewish magazine, once wrote a piece about Bruce for the French satirical publication Charlie Hebdo. He says he learned to speak English while living in Los Angeles during the 1980s, mainly through listening to the comedy of performers such as Bill Hicks and Sam Kinison. When he bought his first Lenny Bruce record, he says, “I didn’t understand a thing. Six months later, I realized he was a comic, a poet, and a philosopher.”

Lenny in a makeshift doctor’s costume with his pregnant wife, Honey Harlow, as she was pregnant with their daughter, Kitty. 1955

After defending his thesis, he traveled to Pennsylvania in 2006 to present Kitty Bruce with a copy. (“Five pounds,” she says. “I weighed it.”) Together they sat down to look through the photo albums compiled by Kitty’s mother, the former showgirl Honey Harlow, and Lenny’s mother, Sally Marr, who was also a nightclub performer.

As the prints tumbled from the clear plastic page protectors, Kitty became increasingly alarmed at how badly many of them had begun to fade.

“She was afraid about the decomposition,” recalls Krief. He suggested she look into the possibility of arranging an acquisition at Brandeis, where the materials would be thoroughly cataloged, climate-controlled, and made available to scholars.

It took some time for Kitty to rationalize parting with her father’s effects. “I don’t feel comfortable letting stuff go,” she explains. “If it has an emotional pull, I hang onto it for dear life. I’m not going to let go of my father twice.”

Until Krief’s suggestion, she hadn’t really weighed doing anything with Lenny’s papers; there was no alma mater or institution to consider. Bruce was born Leonard Alfred Schneider in 1925 and grew up on Long Island in Mineola, just outside Queens. A high school dropout at 16, he joined the Navy during World War II. In 1946, he was discharged after he suggested he was having “homosexual tendencies.” (There has been speculation that Bruce’s later claim that it was a ruse to get out of the service was the inspiration for the cross-dressing Corporal Klinger character in “M*A*S*H.”)

Despite Kitty Bruce’s reservations, the deal with Brandeis was consummated rather quickly after Playboy founder Hugh Hefner, a longtime friend and supporter of Bruce, agreed to make an undisclosed, “generous” gift of the acquisition price to Kitty Bruce. (Hefner’s daughter, Christie, the former chairwoman of Playboy Enterprises, graduated from Brandeis in 1974.)

Kitty Bruce’s reluctance to part with the boxes stemmed in part from the fact that she’d almost lost them once. During a rough period in her life, she was evicted from her New York apartment. At one point some of her father’s belongings were tossed out at curbside, she says, awaiting the garbage truck. The boxes were saved by a neighbor.

As Lenny sank into despair over his legal battles, he also slid deeper into substance abuse. A series of arrests on obscenity charges — in San Francisco, Chicago, and Los Angeles — were threatening his livelihood, as nightclub owners became increasingly reluctant to book the loose cannon of social commentary. During his trial in New York over charges stemming from a series of shows at the Cafe Au Go Go in 1964, Bruce noted the irony in the testimony of a former CIA agent working as a New York City license inspector: “There’s another guy doing my act,” he joked bitterly.

Lenny Bruce died of a morphine overdose in his home in the Hollywood Hills on Aug. 3, 1966. Spector, the music producer, bought the negatives of lurid police photos of Bruce’s naked body lying beside the toilet, to keep them from the press.

Today, Kitty Bruce lives in Pittston, Pa., where she has established the Lenny Bruce Memorial Foundation, which for years operated Lenny’s House, a halfway home, and continues to support men and women in recovery.

Lenny himself came from a broken home, she says, something that became clearer to her the more time she spent with the assortment of memories now in the collection. Sally Marr was divorced from Lenny’s father, a shoe salesman from England named Myron Schneider, when the boy was young. He bounced among various relatives while his mother worked nightclub stages, dancing, telling bawdy jokes, and doing impersonations.

Among the more notable curiosities in the Bruce papers are the comedian’s manuscripts geared toward younger audiences, one of which, “The Rocket Man,” was actually made into a film. There’s also an unpublished manuscript for a thriller called “Killer’s Grave.”

Despite his reputation as a foul-mouthed comedian who baited his adversaries by pushing the limits of “acceptable” language, as his daughter notes, Bruce had a strong faith in American values that revealed a distinct perversity when he felt those values were being corrupted. To Time’s charge that he, Mort Sahl, Tom Lehrer, and a few more of comedy’s new wave of the 1950s were “sick,” he retorted, the true sickness “is that school teachers in Oklahoma get a top annual salary of $4,000 while Sammy Davis Jr. gets $10,000 for a week in Vegas.”

“He was so proud to be an American,” says Kitty. “He had core values, but then there was a flip side to that.”

The Brandeis acquisition was managed by Boston-based entertainment lawyer George Tobia, who has worked extensively with the literary estates of the writers Jack Kerouac and Hunter S. Thompson. He says the deal is “quirky” in that, with no legal heirs in the Bruce family, Brandeis will take full title of copyright protections when Kitty is gone. (While she’s alive, she retains the copyrights; if anything in the collection is licensed for commercial reproduction after her death, Brandeis will be the beneficiary.)

She chose to keep a few of her father’s personal effects, Tobia says, including a trenchcoat, a typewriter, a wristwatch, and a poster for a Thelonious Monk concert, on the back of which Bruce wrote a letter to his friend Ralph J. Gleason, an arts critic for the San Francisco Chronicle whom the comedian considered his Boswell. Those items will likely be on loan to Brandeis when the university mounts an exhibition of its Lenny Bruce collection next year, to mark the 50th anniversary of his death.

Tobia was introduced to Kitty through the veteran comedian Richard Lewis, the “Curb Your Enthusiasm” regular who has often been compared to Bruce for his discursive, neurotic style. For Lewis, as with so many comedians, Bruce’s work has always exemplified the truth-seeking ideal of stand-up comedy: “When I first heard Lenny Bruce’s Berkeley album [“The Berkeley Concert”] at 17 at Ohio State, it was almost like hearing Hendrix’s first album,” Lewis says. “I said, I don’t know totally what this means, but whatever this is, this is the bar.”

Bruce, Lewis says, may be the most important stand-up comic of all for showing his successors — he mentions Lewis Black, Sarah Silverman, and Eddie Izzard, who once played Bruce onstage in London’s West End — how to be fearless.

Lewis has been a friend to Kitty Bruce for decades. He was close to Lenny’s mother, too: Sally Marr, who died in 1997, had a poster of Lewis’s Carnegie Hall concert hanging in her apartment, right next to the poster from Lenny’s own appearance there.

“Very surreal,” Lewis says.

As a token of affection, Kitty once gave him one of Lenny’s handwritten notes to Gleason. In it, Bruce enthusiastically relates that he has just finished a gig at a Milwaukee nightclub and expects to be invited back.

“Forget about his breakthroughs, his courage, his amazing material,” says Lewis. “His First Amendment battle aside — and that’s a big aside — he was still just a working comic, looking for bread.”

A half-century after Bruce’s death, Brandeis’s establishment of the Lenny Bruce Archive might be the “attaboy” that eluded him in life.