Robert Weide was still at high school in California when he volunteered to teach a class on the novels of Kurt Vonnegut. “There were maybe a dozen people in the class. We had tests, and people did papers and I gave grades and all that, so it was like a really cool Vonnegut book club,” he recalls. Never mind that Breakfast of Champions, the illustrated novel that had introduced him to his hero a couple of years earlier, wasn’t exactly conventional high school fare. “To give an idea of the maturity of my illustrations for this book,” it typically reads, “here is my picture of an asshole.”

Weide still has the paperback that he read back then. He flicks lovingly through its yellowing pages in a film that has taken him 40 years to make. Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time isn’t exactly a conventional documentary. It’s both a portrait of an author over a lifetime and the story of a friendship that grew out of fandom over decades of letters, recorded speeches and snatched interviews.

Its unusually long gestation means it has also accumulated a sub-theme as a chronicle of changing technologies, from the home movies of the 1920s and 30s that Vonnegut’s parents made of their three blond children, romping around the lawn of their prosperous Indiana home, through fuzzy VHS recordings, faxed images and scratchy phone messages. All have been carefully catalogued and preserved in the Los Angeles house where the director lives with his wife, the actor Linda Bates.

Weide grew up in Fullerton, California, the precociously nerdy son of a Jewish family, who was hunting out Laurel and Hardy and Buster Keaton films at a time when his schoolmates were dreaming about playing in the Super Bowl. “Sports wasn’t my thing,” he says. “The Marx brothers were sort of my gateway drug, and opened the door to that whole world of comedy at a fairly young age.” He has since made a specialism of documentaries about comedy greats, including WC Fields, Lenny Bruce and Woody Allen. He directed a not-entirely-successful adaptation of Toby Young’s Hollywood prat-fest How to Lose Friends and Influence People, starring Simon Pegg, and was lead director on the extremely successful TV sitcom Curb Your Enthusiasm, starring Larry David as a semi-fictionalised version of himself.

Vonnegut was an ageing celebrity, working the inspirational speaking circuit in the absence of literary inspiration, when Weide wrote to him suggesting that he would like to make a documentary about him. His calling card was a film about the Marx brothers, which he had made while still at college. “I waited and waited and got no response, so I thought, well, that’s it, and then suddenly there was a letter with that familiar handwriting on it that you see in Breakfast of Champions,” Weide says. “I was 23 and he was about to turn 60 and I’d refer to him as the old man. Now I’ve just turned 63. How fucked up is that?”

Until his mid-40s Vonnegut was an unsung author of magazine short stories and easy-to-read novels. He had given up a day job working for General Electric to find himself struggling to feed a large family comprising three of his own children and four of his sister’s, whom he and his wife, Jane, adopted after their parents died within days of each other. That all changed in 1969 with the publication of his masterpiece, Slaughterhouse-Five, the novel he had been struggling to write all his adult life. It revisited his experiences as a prisoner of war in Dresden when the German city was firebombed in the second world war, striking a chord with a generation newly traumatised by the war in Vietnam.

Like his protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut survived by hunkering down in the meat lockers of an old slaughterhouse. “There were sounds like giant footsteps above. Those were stickers of high explosive bombs. The giants walked and walked.” Like Pilgrim, he and his fellow PoWs emerged to find themselves tasked with digging thousands of charred corpses from the ruins of the city. The film includes some grim archive footage. Yet, interviewed by Weide during a train journey to a speaking engagement, Vonnegut shrugs it all off. “I didn’t feel much of anything,” he insists. “It was a great adventure of my life … The neighbourhood dogs when I grew up had far greater influence on what I am now than the firebombing of Dresden.”

The camera then flicks to his two daughters, Nanette and Edith. “Did he really say that?” asks Edith in astonishment. Inappropriate laughter was his way of processing the horror, Nanette points out.

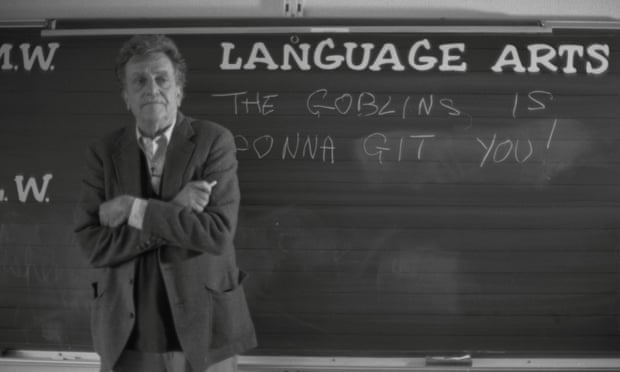

Weide takes Vonnegut back to visit his old school, where he gazes up at the lists of the dead and wheezes like a set of merry bellows as he recalls the randomness of some of the deaths. One college contemporary, he chortles, was so excited on hearing about the bombing of Pearl Harbor that he banged his head on the faucet of his bath and died.

The theme of inappropriate laughter echoes through the film, from the minute Weide tracks down the schoolteacher who first introduced him to Breakfast of Champions. “Looking back now, I’m horrified that I did it. It’s a fairly edgy, iconoclastic book,” she says. No historian of comedy could remain immune to this issue, Weide points out. “Would Lenny Bruce be acceptable today? I’ve given that a lot of thought, and I think all the people who are always saying ‘Where’s Lenny Bruce now?’ would cancel his ass after about five seconds on stage. People still revere him as a groundbreaker, a social satirist, speaking truth to power and all that, but I don’t think he’d last 10 minutes these days.”

Vonnegut’s get-out in Slaughterhouse-Five was the catchphrase “And so it goes”, which ricochets around the novel 100 times. This becomes a mantra for Weide’s film, too, as it becomes ever more darkly autobiographical. “I used to worry that the friendship would get in the way of the film, but later on I began to fear that the film would get in the way of the friendship,” he says. His solution was to draft in a co-director, Don Argott, to add a second strand. “I didn’t even want to be in the film,” he insists. “This was going to be a conventional author doc with interviews with Kurt, his family, biographers and scholars. But when you take almost 40 years to make a film, you owe some explanation.”

The tale of Weide’s friendship with Vonnegut segues into the story of his love affair with Linda, who appeared in an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, and now has an aggressive form of dementia. Vonnegut adored Linda. “He would have met her a couple of years after I did, and he said, ‘You know, this one’s a keeper. When are you going to marry her?’ So I did marry her, in 1998.” Vonnegut also said he would only visit the couple if Weide directed her in a revival of his 1970 play, Happy Birthday, Wanda June (in the part played by Susannah York on film a year later, opposite Rod Steiger).

Weide duly did so at a Hollywood theatre in 2001, though the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center prevented its author from keeping his side of the bargain. “The film is just a continuation of that thread. He was a big part of the fabric of our lives,” says Weide. Vonnegut died after a fall in 2007 at the age of 84. “And then this happened with Linda, which was affecting my ability to even focus on the film,” says Weide. “The thought was gnawing at me that I need to reveal this and talk about what we’re going through.” Twelve years after Vonnegut’s death, the couple renewed their vows on film and, in one of the final scenes, they stroll hand in hand along an esplanade. “Linda is far more disabled now,” he says. “She can’t walk. She can’t speak. She can’t feed herself. And so it goes.”

What saves this meta-story from self-indulgence is its echo of Vonnegut’s own self-referential storytelling, not least through the recurring, autobiographical figure of Kilgore Trout, the unsuccessful author of 117 science fiction novels, a multiple-eyed portrait of whom hangs on a wall in the Weide home. Vonnegut wrote versions of Trout into novels and short stories over more than five decades.

In his final novel, Timequake, he set Trout free, naming Weide as one of the guests at the clambake thrown to celebrate the occasion. Weide, his friend, archivist and chronicler, now sets Vonnegut himself free as a 20th-century magus who looked up at the stars and laughed at the terrifying randomness of everything beneath them. As an extraterrestrial Tralfamadorian tells Billy Pilgrim in Slaughterhouse-Five: “Why me? That is a very earthling question to ask Mr Pilgrim … because here we are, bugs trapped in the amber of this moment. There is no why.”