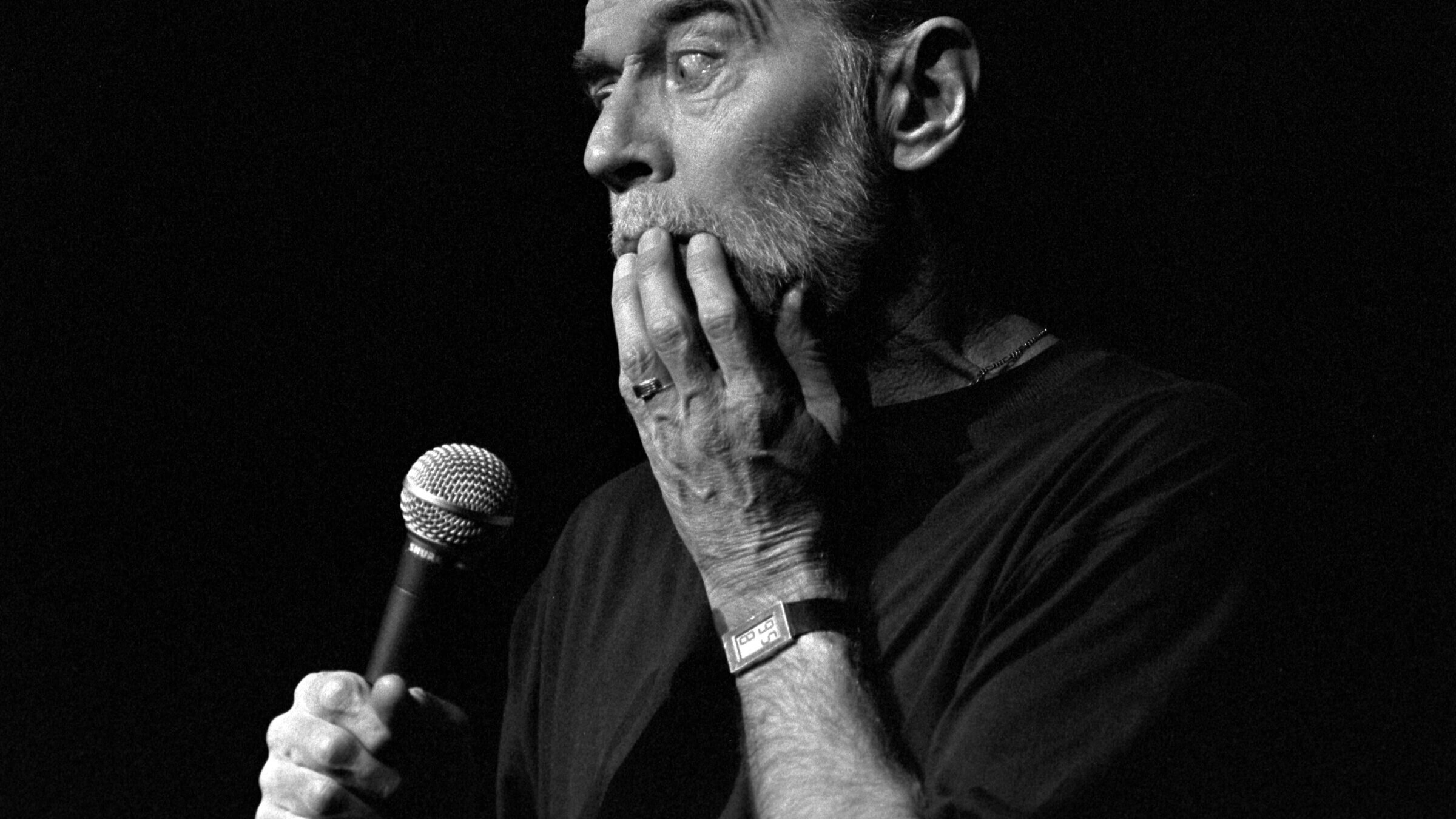

On his classic album, stand-up comic George Carlin identified a septet of forbidden words. Photo by Getty Images

“Class Clown!”

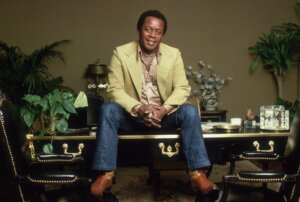

That’s all you needed to say back in 1978 to get a nod of approval and a welcoming five-slap from me and my sixth grade friends. We were all heavily into comedy records at the time — Flip Wilson, Redd Foxx, Richard Pryor, Cheech & Chong and Steve Martin were just a few of the comics whose albums we spun religiously. But within our little circle, it was taken as a matter of stone-cold, irrefutable fact that not only was George Carlin the best of them all, but that his album “Class Clown” was the greatest stand-up comedy album of all time.

It didn’t matter to us that “Class Clown,” released in 1972, was already over 5 years old by the time we discovered it. We didn’t know that the album had put Carlin on the map as a countercultural icon after a decade-plus of white bread-oriented comedic graft; nor did we realize that Carlin had already begun a slide (albeit a thankfully temporary one) into self-parody and dwindling relevance by the time our gang got hip to him. All we knew is that the record made us laugh hysterically whenever we put it on.

Watching Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio’s new two-part HBO documentary “George Carlin’s American Dream” — which, among other things, nicely pinpoints why ”Class Clown” was such an important milestone in Carlin’s long and winding career — inspired me to go back and listen to the album for the first time in at least 30 years. Stand-up comedy doesn’t always age particularly well, especially after half a century; but I’d remained a fan of Carlin and continued to follow him up until his death in 2008, so I figured “Class Clown” would still have the power to crack me up. Ultimately, however, I was looking less for laughs than for a greater understanding of why the album had resonated so deeply with me and my friends at that early stage of our adolescence.

After all, Carlin was a street-smart New Yorker who had just turned 35 before recording “Class Clown” in front of a live audience of (probably very stoned) Southern Californians at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium; we, on the other hand, were a bunch of 11- and 12-year-old middle-class kids growing up in the college town of Ann Arbor, Michigan. Most of us were Jewish, and we all attended public elementary school; and yet, most of the routines I recalled from the album pertained to Carlin’s early education at a Catholic parochial school. Not only did I not know any Catholics back in those days, but I also had only the vaguest idea of what Catholicism even was — I knew that nuns were involved, but not much else. Nonetheless, I vividly remembered us laughing almost as hard at Carlin’s riffs on such alien-to-us concepts as confession, purgatory and not eating meat on Fridays as we did at his dissection of things more pertinent to our own existence, such as the making of artificial fart noises.

Indeed, it was surely the latter subject that initially endeared Carlin to us. Our sixth grade classroom was a veritable Olympiad of armpit and elbow farts (one of my classmates could even make them with the back of his knee, much to our collective admiration and delight), so we completely understood when Carlin spent much of the album’s opening title track recounting how important it had been to have such things — along with knuckle cracking, belching, and the ability to make others spit liquid through their nostrils during lunch — in his personal class clown arsenal.

And if we needed further proof that this guy was speaking our language, side one of the album also contained his hilarious ruminations on store-bought novelties like whoopee cushions, fake vomit and plastic dog turds, items which were very near and dear to our own hearts (and took up considerable space in our classroom desks) back then.

One of the things that “George Carlin’s American Dream” makes wonderfully clear is that, even as road stress and cocaine abuse aged him well beyond his years, and even when he began to focus on darker, more aggressively cynical material toward the end of his life, Carlin never lost touch with his rambunctious inner child. And since we were rambunctious actual children at the time, we were of course all-in on any adult who could still unashamedly identify with the sorts of puerile obsessions that were then firing our imaginations.

But upon listening to “Class Clown” again, it was initially a little harder for me to put my finger on why we loved side two almost as much as side one. The first four tracks on the album’s second half — “I Used to Be Irish Catholic,” “The Confessional,” “Special Dispensation” and “Heavy Mysteries” — all draw heavily on his religious upbringing, while “Muhammad Ali, America the Beautiful” is an acerbic commentary on such decidedly “adult” topics as the U.S. government’s mistreatment of the boxing legend during the Vietnam War, how the American media and U.S. industrial interests were complicit in that war, and how the U.S. had brutally exploited both its natural resources and its native populations since the early days of its existence. We were definitely not the target audience for this material, yet I can vividly recall us hanging on every word, and laughing knowingly at most of the punchlines.

The appeal of the album’s closing track, “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” was pretty obvious, however — I mean, he actually said those words on the record! Of course, we had no clue that the bit had been inspired by Lenny Bruce (hell, we had no clue who Lenny Bruce even was at that point), or that Carlin had been arrested for “disturbing the peace” after reciting it at Milwaukee’s Summerfest in 1972. (One of the most amusing highlights of “George Carlin’s American Dream” comes when the case against Carlin goes to trial, and the presiding judge has to cover his face to keep the court from noticing that he’s laughing at Carlin’s jokes.)

Nor did we have any idea that a complaint involving a radio broadcast of “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” would eventually result in FCC v. Pacifica Foundation, a July 1978 U.S. Supreme Court decision upholding the power of the Federal Communications Commission to regulate broadcast media. But we didn’t need a greater context to see Carlin’s point about the absurdity of banning the use of certain words, or to endlessly repeat his riff on “two-way words” on our school playground.

“Remember the ones you giggled at in sixth grade?” he asked, referring to words like cock, balls and prick. Hell, we’d already been giggling at them for years; some of my friends had even been thrown out of our fifth grade music class for snickering a little too loudly at the “now we don our gay apparel” line in the Christmas carol “Deck the Halls.” “That is not funny,” our music teacher had lectured us, her jaw clenched in grim disgust. “There’s the kind of gay that’s nice, and then there’s the kind of gay that’s… not so nice.”

I think that last memory, which came flooding back as I was relistening to “Seven Words,” pretty much sums up why my friends and I responded so powerfully to George Carlin in general, and to “Class Clown” in particular. We were young and somewhat sheltered, but as children of Watergate and the Vietnam War era we’d still already witnessed (and internalized) more than our fair share of adult hypocrisy and awfulness, both on the news and in person — and here was an adult who was calling all of it out in ways that we could understand, relate to and laugh at, even if his specific reference points weren’t necessarily ours.

We were smart (and smart-alecky) kids still learning to fully express ourselves verbally, and thus delighted by Carlin’s whimsical wordplay and his humorous acknowledgement of the weird inconsistencies that existed within both the English language and the American media’s deployment of it. And sure, we laughed at the swear words and the mentions of bodily functions, but even those bits served a higher purpose, communicating to us that the “childish behavior” for which we were often admonished could serve as fuel for inspiration in our adult lives.

“George Carlin’s American Dream” is not without its issues. It’s probably a half-hour too long (a Judd Apatow trademark, after all), some of the talking heads don’t add anything to the story, and the film occasionally meanders in ways that unfortunately cloud the chronology of Carlin’s career. Still, I am profoundly grateful that the documentary has reacquainted the world with the thought-provoking brilliance of George Carlin, just as it transported me back to the days when “Class Clown” both confirmed and expanded my outlook on life. And anyway, it’s always helpful to be reminded that, in Carlin’s immortal “Seven Words” words, “You can prick your finger, but don’t finger your prick.”