Back in the days when they were still called comediennes, an older comedienne turns to a younger one and says: “What is your persona?” The younger woman is confused. Bob Hope and Lenny Bruce don’t have personas, she says. They are just allowed to be funny as themselves, so why isn’t she? “They have dicks,” snaps back Sophie Lennon, one of the most memorable characters in The Marvelous Mrs Maisel.

In the hit Amazon show – set in 50s and 60s New York – Midge Maisel discovers her talent as a standup. She’s an accidental comic, getting up on stage at a Greenwich Village club one night, drunk and angry and confessional, after her husband leaves her for his secretary. At the time, there is really only one mainstream female standup: Lennon, whose persona is that of a Queens housewife, complete with feather duster, fat suit and grating catchphrase. Maisel, with her shocking, electrifying set – it ends with her getting arrested – represents a new style of comedy, particularly for women.

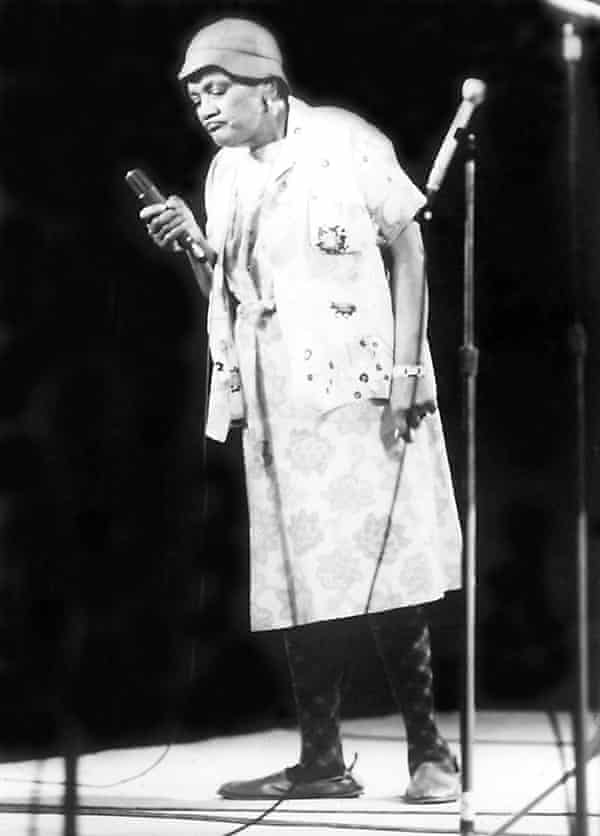

Lennon and Maisel have been likened to real-life comics Phyllis Diller and Joan Rivers (the show’s creator, Amy Sherman-Palladino, has said Maisel is more of an amalgam of lots of people, including her father who was a standup). When Jane Lynch, who plays Lennon, read the script, she thought of Diller, whose act was a caricature of a 50s housewife. There had been others, such as Belle Barth, Rusty Warren and Moms Mabley. In 1939 Mabley, who had come from the black vaudeville circuit, became the first female comic to perform at the Harlem Apollo (the third season of Maisel features Mabley, played by Wanda Sykes, performing there). Mabley had a grandmotherly housewife persona but was more edgy than Diller, her act confronting gender and racial prejudice. It was Diller, though, who became the first female comic superstar.

“In order to break through,” says Lynch, “you had to have material that spoke to men, because the club owners, the TV producers and the late-night hosts were men. You would cater your material to what they would think is funny – and something that men love is when it refers to them. You go, ‘I can’t get a boyfriend cos I’m ugly’ and right there you’re not threatening. You’re almost one of the guys, because the guys don’t want to go to bed with you.” Lynch’s character explains this problem to Maisel, referring to her beauty. “Men don’t want to laugh at you,” she says. “They want to fuck you. You can’t go up there and be a woman. You’ve got to be a ‘thing’.”

Modern viewers can immediately tune into Maisel’s material about sex and the challenges of motherhood, as well as her sweary rants, all delivered in up-to-date dialogue. It’s not meant as a historical record, points out Yael Kohen, author of We Killed: The Rise of Women in American Comedy. “I think there is an aspect of the comedy and her point of view that is very modern,” she says, “and it’s being imposed on someone in that time period.” Whereas at the time, the comics who became successful, such as Diller and Rivers, were not “necessarily defying female stereotypes. Joan Rivers was joking about getting a husband.”

In reality, it would be some years after Maisel’s debut that more subversive, intellectual comics such as Lily Tomlin would take off. There had been other women whose acts didn’t rely on a comic lack of self-esteem, such as Elaine May, but she was in improv, not standup. Diller told Kohen she wore a sack dress partly because looking funny was part of the act, but also “because I had such a great figure”. Kohen says: “There’s long been a tension between women’s looks and their sense of humour – this idea that a funny woman couldn’t be beautiful.”

Rivers, with her black cocktail dress and pearls, challenged this to some extent. In her book, Kohen quotes a 1963 review of Rivers’ early act: “Female comics are usually horrors who de-sex themselves for a laugh. But Miss R remains visibly – and unalterably – a girl.” But, points out Kohen, Rivers was not a conventional beauty in the way Maisel is. “She cared about how she looked and she used that in her comedy, but it doesn’t mean the tension [between being beautiful and funny] wasn’t there.”

It is also, adds Kohen, “not irrelevant” that Mrs Maisel is Jewish. “Many of the most famous women in comedy from the 1960s on were Jewish. It’s important to note that these women weren’t considered emblems of Wasp femininity. They were considered part of an ethnic minority and not conventionally beautiful. Jewish women were often considered an exception to the rule that women aren’t funny – Christopher Hitchens, for example, singled them out in his infamous essay Why Women Aren’t Funny. And it wasn’t always a compliment.”

In the 60s, Treva Silverman – who would go on to write for The Mary Tyler Moore Show but was rejected for Johnny Carson because she was a woman – was writing sketches for Upstairs at the Downstairs, the New York nightclub where many comics and musicians started their careers. “With topical revues,” she says, “nobody cared if it was a man or a woman. It was more of a cabaret atmosphere. There was not the kind of sexism there was with standup. My doing sketches was not that unusual for a woman.”

Silverman and Rivers became friends. “Joan was so ambitious from the very beginning,” says Silverman. “She was in touch with absolutely every agent and they were not used to booking a female comedian. People would say ‘Well …’ and her agent would say, ‘Try her for one night’ because they knew that would mean booking her for a week.” What were Rivers’ early audiences like? “They would think, ‘What is she doing up there? She should be home stirring the omelette or whatever.’ But she was so likable. Men liked her immediately, because she was very pretty, even though she kept complaining she wasn’t.”

Her act, says Silverman, “was absolutely from a female perspective. She talked about what it was like to be a woman, an unmarried woman when everybody else was doing the ‘right thing’. She was talking about feeling inferior, somewhat unattractive, being the odd person in not only a male-dominated world, but also not up to par with the rest of the women. But everything she complained that she didn’t have, of course she had.” In putting herself down, says Silverman, “she kind of knew that she would be more likable”.

Robin Tyler was part of a double act in the 60s with her partner Patty Harrison. “Humour is the most aggressive medium there is,” she says. “The only way women were allowed to be aggressive is when they turned it on themselves. So you have Phyllis Diller and Joan Rivers with, ‘I’m not pretty enough.’” Tyler says she understands it, “because that’s what they had to do to make a living”. Diller told Kohen: “Women’s libbers hated what I was doing. They didn’t like my self-deprecation.”

Harrison and Tyler had started joking about things like bra sizes, but then second-wave feminism took off. They read Betty Friedan’s 1963 book The Feminine Mystique and it felt like a wake-up call. “We said, ‘Why are we making jokes on ourselves?’” Women, continues Tyler, were questioning “what we thought was funny. Patty and I turned it around and did ‘Take my husband’ and ‘I don’t have penis envy – I have 12 at home in a drawer.’” This was towards the end of the 60s and reviews of their work called them threatening to men. “All we did was take the same material [male comics were doing about women] and turn it on men.”

Tyler enjoys The Marvelous Mrs Maisel, which has just started its fourth series, not least because it echoes some of her own career, in particular when Maisel and her family go on holiday to the Catskill Mountains, where popular resorts attracted affluent Jewish families. “I used to perform as a singer in ‘the Borscht Belt’. The comics there, I loved them, all the Jewish comics, but it was still sexist.”

Like Maisel, Harrison and Tyler performed for US troops but, unsurprisingly, their feminist act did not go down as well as Maisel’s funny – but extremely feminine – material. On a comedy tour in New Zealand, Tyler says the man who booked them for one gig was so angry that they were encouraging the women in their audience to organise liberation movements, he shot at them. “We aggravated a lot of people because not only were we funny on stage, we were activists off stage. And they had never seen women use comedy as a weapon.”

They mostly played colleges, rather than clubs. “Why would we want to play clubs where we played to sexist audiences? We were never going to end up in Vegas.” In the 70s, they made an attempt to go more mainstream when they were approached to make TV, but they didn’t fit. Tyler remembers getting a call from Fred Silverman, the influential TV executive. “We said, ‘We’re lesbians.’ He said, ‘That’s OK. Just don’t tell anybody.’ They were trying to make us do stupid sketches of stupid women and we hated it. They made four pilots with us, and it didn’t work out. Not only were we women-aggressive, we were lesbians-aggressive, so that was really too much.”

TV, she says, was like an extension of the comedy circuit. “It wasn’t just sexist. They had to neutralise us.”