By Harvey Blume

One reason Fred Waitzkin’s work, outside of Searching for Bobby Fischer, is not as well known as it might be is that it doesn’t respect time-honored boundaries between fiction and nonfiction.

Filmgoers and readers alike have heard of Searching for Bobby Fischer. First there was Fred Waitzkin’s memoir of his chess prodigy son and then came the popular 1993 movie adaptation, which was recently featured on Netflix’s most popular list.

Filmgoers and readers alike have heard of Searching for Bobby Fischer. First there was Fred Waitzkin’s memoir of his chess prodigy son and then came the popular 1993 movie adaptation, which was recently featured on Netflix’s most popular list.

When I spoke to Waitzkin by phone recently, he said, “Here’s a funny story about that book. A few days before it was released in 1988, my editor said: a warning, Fred, about the book business. Don’t expect big sales from your memoir. There are just too many books out there. The shelf life of a book today is halfway between milk and yogurt.’

“That, Waitzkin added, “was 33 years ago.” He took a certain glee in pointing out that the book “has had an astounding publishing life.” It is now number on the Amazon best seller list in several categories.

Waitzkin followed that volume with a profile of Gary Kasparov, Mortal Games: The Turbulent Genius of Garry Kasparov. Between them, these books provide some of the best accounts of chess life, from looking at exalted championship matches to the peccadilloes of the players. Kasparov, for example, shows off his newfound ability to do handstands — in the sometimes grimy quarters where the game of chess thrives and proliferates.

One reason Waitzkin’s work — outside of Searching for Bobby Fischer — is not as well known as it might be is that it doesn’t respect time-honored boundaries between fiction and nonfiction. This presents a problem for critics and reviewers who aren’t quite sure how to peg him.

As for his fiction, the characters in Waitzkin’s first novel, The Dream Merchant (2013), floored me, from its protagonist, Jim, to his counterpart, the brilliant but repellent Marvin Gessler. There is a strong element of eroticism in the narrative: Gessler is apt to literally foam at the mouth with lust while Jim naturally glides from one affair to another. But Waitzkin’s real subject, as in most of his work, whatever the genre, is heroism of one sort or another, and Jim is the author’s prototypical hero.

Part of the allure of Dream Merchant for me is that it is deeply concerned with the effects of aging. Jim is in his 80s but commits to taking actions that defy his advanced years. For example, he enters into a revivifying love affair with a decades younger Israeli woman. Is that a bit much? Is it unbelievable? It might be in the hands of a lesser writer.

In the new novel, Strange Love, we see yet again how an older man longs to be reborn by romancing a younger woman. But females are the heroines of this short, affecting novel. Rachel, the central character, is a gifted storyteller; she lives an impoverished and isolated life in a tiny village on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. She tells her stories to the seabirds until she meets the narrator, a moderately successful novelist in his youth who has dried up. These days his no longer solicitous editors do not return his calls.

Fleeing New York, the author discovers the lost village of Fragata, which lives up to its traditions of unbridled sexual abandon and vivid superstitions. Rachel’s stories mesmerize him. He hopes to make Rachel his lover and muse but, by the end of the book, the novel’s muse has become the artist, molding the narrator.

The Dream Merchant is a densely written work, while Strange Love‘s prose style is more cinematic, sparse, drawing on short sentences. It is as if the author, like some of his characters, has reinvented himself. The story draws on the brusque energy of a movie script, its action moving from marlin fishing to the basements of New York, where the narrator, unable to find other employment, takes up the trade of exterminator.

I enjoyed the following exchange — ranging from chess to Hemingway — with Waitzkin.

Arts Fuse: What drew you to the subject of chess in the first place?

Fred Waitzkin: Chess initially intrigued me when Bobby Fischer played Boris Spassky for the world championship in 1972. Along with half the country I watched the match on PBS, hosted by Shelby Lyman and Bruce Pandolfini, who later became one of my closest friends.

Fred Waitzkin: Chess initially intrigued me when Bobby Fischer played Boris Spassky for the world championship in 1972. Along with half the country I watched the match on PBS, hosted by Shelby Lyman and Bruce Pandolfini, who later became one of my closest friends.

AF: The game fascinated you?

Waitzkin: I won’t write about a subject unless I’m greatly attracted to it. If I’m in love with a story or character, there’s a decent chance my readers will connect with my writing.

Thirty years ago, when I was writing freelance features for the Sunday Times Magazine and New York Magazine, I’d regularly have story meetings with editors. I don’t believe I ever wrote a single piece that was suggested to me. Passion for the story was the key for me then as it is now.

AF: Did you play chess?

Waitzkin: When I watched the Fischer-Spassky match I was riveted by my absurd belief that I would myself soon play games like Bobby. I began playing chess against my friends, most of whom had a little knowledge of the game, so I won.

One afternoon I went to the Rossolimo Chess Shop in Greenwich Village and launched into a game against a pimply adolescent who read the newspaper while I pondered [the game] deeply, like Bobby Fischer. This kid beat me while rarely glancing at the board.

AF: I share your pain, as in I once shied away from playing this guy who was more concerned with eating his napkin than with worrying about his next move.

Waitzkin: That game with the pimply adolescent jolted me into retirement for 10 years until my six- year-old kid, Josh, pleaded with me to play with him. For a couple of months, I battled with him on the kitchen table, sweating out our games, while he played with his toys in the living room until I finally made my move. One day I was so slow to move that Josh took a lengthy bath with his tub toys. He worked out the moves to checkmate in his head.

That forced me into a second retirement from play and I began writing about the game.

AF: So chess, despite it all, retained its allure?

Waitzkin: I wrote almost exclusively about it for about 10 years. After I wrote Searching for Bobby Fischer I wrote Mortal Games, the biography of Garry Kasparov. I wrote freelance pieces about other chess players, and co-authored a column with Kasparov. I loved writing about chess players. They were so unusual and brilliant.

I stopped doing that because of Josh, who retired from play, when he was about 20. One day he came to me and said, “Dad, it’s time to stop writing about chess. If you don’t stop now you’ll write about it for the rest of your life. You’ll be like one of the guys in the Rossolimo Chess Shop.”

I took his advice and stopped.

AF: In the past you have been drawn to male figures — Jim in The Dream Merchant, Kasparov in your profile of him. I might even mention your son Josh in Searching for Bobby Fisher. But in Strange Love you turn to the women’s side of things — their aspirations, intelligence, and daring.

Waitzkin: I didn’t set out to write about women. I knew that Rachel was a great storyteller and that her sister was very beautiful and had a complicated sexual history. I just wrote the stories and tried not to overthink it.

Some authors become addicted to the creative energy born from a new, often much younger, lover. For Ernest Hemingway and Philip Roth, for example, remove their passionate relationships and one might venture that their greatest books might never have been written.

In Hemingway’s case his best writing mostly took place in the early months of each relationship with a new wife. Yet, he was awful to these women, dominating them with psychological and physical cruelty as if eating them alive for his art; then moving on to the next feast.

In Strange Love, the narrator has been washed up as an author for three decades before he discovers Rachel, 30 years his junior and a profuse creative storyteller. But she is without any outlet for her calling besides reciting to the seabirds on a deserted beach in Costa Rica. He worships her beauty and youth. Mostly, though, it is her undiscovered talent, the very gift he longed to have himself. But unlike Roth and Hemingway, the narrator in Strange Love is dominated by this younger woman in all respects. Unlike the ladies quietly whispering encouragement to Roth and Hemingway from the wings, Rachel is in every sense the power figure in this love story.

AF: Tell me something about how you write, how you move between nonfiction and fiction with such ease.

Waitzkin: Graham Greene said somewhere, I believe it was in a biography, that everything he wrote in novels was grounded in his personal experience. This is true for all serious authors. My last three books were novels. But in each I introduced “real characters” within the tapestry of characters that many would consider wholly fictitious. It creates an interesting dance. My real characters like Lenny Bruce and Sammy Davis Jr. enhance the fictional landscape, create circumstances — often extreme ones — where my fictive characters fully come to life. I’m thinking, for example, of Ava’s love affair with Lenny Bruce in The Dream Merchant. Bruce, I believe, brings out the very best of Ava.

None of my characters is wholly fictitious. I usually have someone in mind when I’m beginning to draw a character, and then I allow him or her to develop within the intricacy of the story. That’s the only way I know how to do it.

AF: It took you almost 10 years to write The Dream Merchant and yet you were able to write Strange Love in half a year.

Waitzkin: Many years ago, I read an interview with Hemingway who said something that stopped me in my tracks. He said that each working day he attempted to write better than he was capable of writing. I had no idea what he meant by this. Then about 10 or 12 years ago, I got it, or believed I did. Hemingway was talking about discoveries he made in fast writing.

For years I was a very slow writer, each sentence felt precious and hard fought. Then I started experimenting, writing sections of stories very quickly, almost more rapidly than I could think. I discovered that ideas and new directions in plot, themes, and character appeared like magic. Some of the best ideas in me, deep inside where they lay unnoticed, came from this rapid writing.

AF: You’ve had media contacts, most notably with David Milch, best known for his spectacular cable show, Deadwood, and Hill Street Blues. Were you ever tempted to follow that path?

Waitzkin: Milch and I were friends when he was teaching at Yale. Poet and critic Robert Penn Warren said that Milch wrote dialogue better than anyone in America — he said this before David had published a thing.

On one of my visits David asked me to read his screenplay about horse racing, which I still remember today. So alive and menacing it took my breath away.

When Searching for Bobby Fischer opened in L.A., David came to the opening and the next day invited me to the set of Hill Street Blues. He offered me a one year contract for crazy money. I brooded about it for a month and finally turned him down.

AF: Do you ever regret that decision?

Waitzkin: I thought about it on and off for a few months. I would have needed to move to L.A. with my family and I was enjoying the chess life with Josh too much. Also, I thought maybe I’d have one good script in me but couldn’t imagine churning them out each week. In that world it is just so easy to be sucked into the money and glamour.

Probably Milch would have written a great novel if he could have turned down the bright lights for a while.

AF: Do you have any idea of what you’ll be working on next?

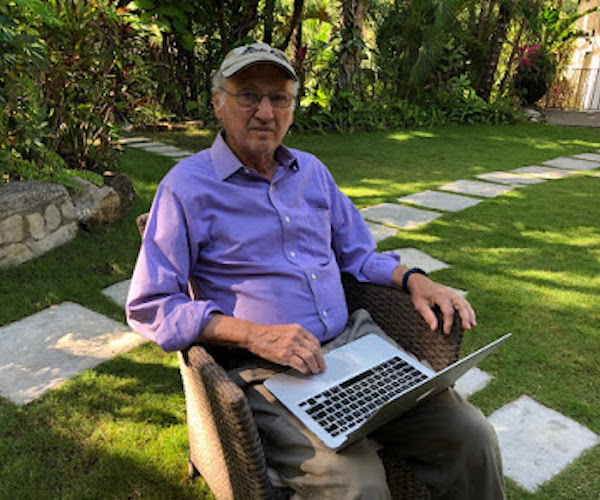

Waitzkin: A harrowing question. Whenever I finish a book, I’m haunted by fear that there will never be another for me, and then what? I’ll just be a guy walking the streets or listening to sports talk radio.

In the weeks after finishing a book, whatever notion I might have about a new one is subsumed by the last one. Instead of the new story, I find myself revisiting a page I’d written in the last book or composing a new chapter that might have been included. It’s maddening that I do this.

So, I need to give myself some time to separate. Then I need to run into someone who stirs me deeply or a story that makes the hair stand up on my arms, something that jolts me from lethargy and the fear that there will be no more books for Fred.

Because, one day, there really will be no more books in Fred.

Harvey Blume is an author—Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo—who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in the New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, American Prospect, and the Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to the Arts Fuse, and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.