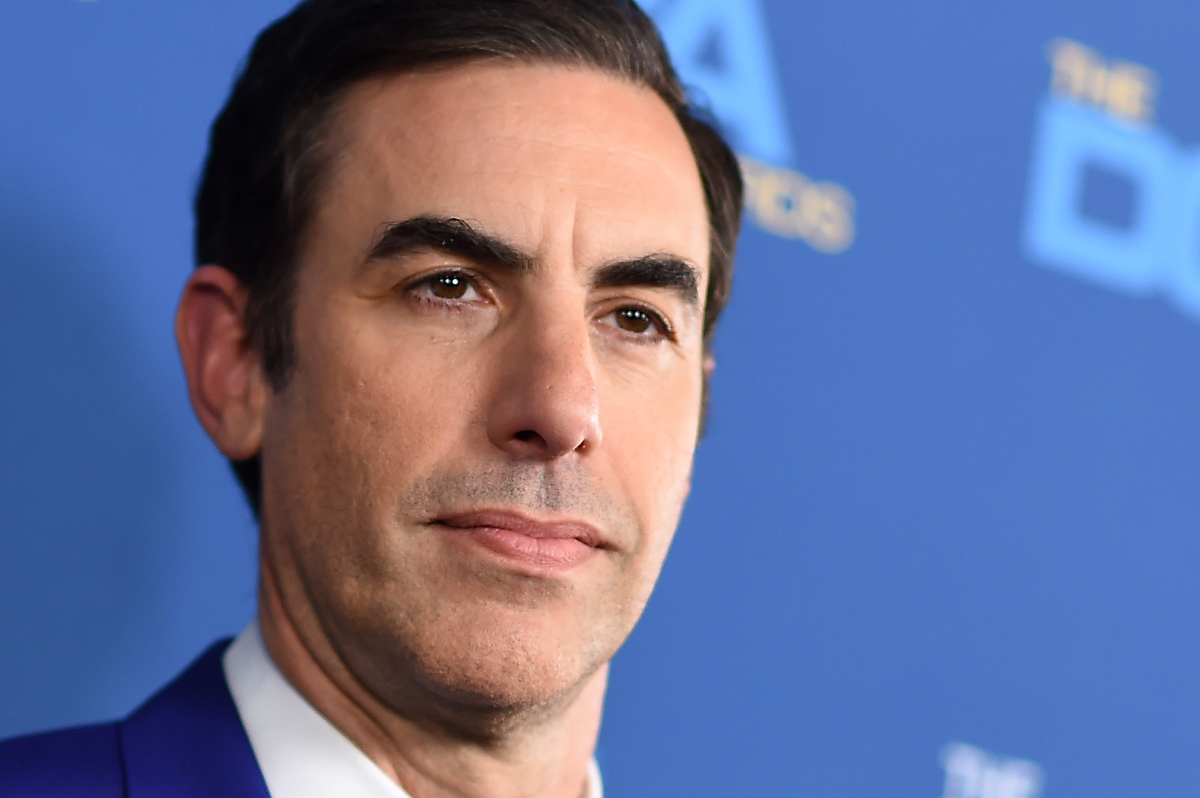

Sacha Baron Cohen, shown here in 2019, has been nominated for three Golden Globe Awards: two for acting in and producing Borat Subsequent Moviefilm and another for his supporting actor role in The Trial of the Chicago 7. Valerie Macon/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

Valerie Macon/AFP via Getty Images

Sacha Baron Cohen, shown here in 2019, has been nominated for three Golden Globe Awards: two for acting in and producing Borat Subsequent Moviefilm and another for his supporting actor role in The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Valerie Macon/AFP via Getty Images

British actor Sacha Baron Cohen is known for creating absurd characters and then bringing them into the real world — and for interacting with people who have no idea the characters aren’t real.

Nearly 20 years ago, he created the character of Borat Sagdiyev, a dimwitted, anti-Semitic, sexist TV journalist from Kazakhstan. The 2006 film Borat aimed to expose American bigotry, xenophobia and sexism as the title character’s unwitting scene partners reveal their true beliefs.

The film was an international success, making Borat a widely recognizable, highly quotable fixture of pop culture. Baron Cohen assumed the jig was up: Once the world understood that Borat wasn’t real, there would be no way to interact with the public like before.

But when Donald Trump was elected president and there was a rise in anti-Semitic, racist, xenophobic rhetoric, Baron Cohen decided to revive his signature character.

“I felt very clearly from the start of the [Trump] administration that we were heading towards authoritarianism. And so I felt I had to do something,” he says. “I was terrified that if Trump got in again, that America would be a democracy in name only.”

In Borat Subsequent Moviefilm, which was released on Amazon in October, the character returns to America to offer President Trump a bribe. When it becomes clear that Borat will not meet the president, Borat tries unsuccessfully to give his 15-year-old daughter (played by Maria Bakalova) to Vice President Pence as a gift. He then settles for giving her to Rudy Giuliani, which ends in a now infamous scene in a hotel bedroom.

Baron Cohen has been chased, nearly arrested and sued during his filmmaking process. While filming at a gun rights rally for the Borat sequel, Baron Cohen was afraid for his life. He thinks it’s time to retire the undercover characters.

“At some point, your luck runs out. And so I never wanted to do this stuff again,” he says. “I can’t.”

Baron Cohen has been nominated for two Golden Globe Awards for his role producing and starring in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm. He has also been nominated in the best supporting actor category for playing Yippie leader Abbie Hoffman in the Netflix film The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Interview Highlights

On fearing for his life at a gun rights rally while filming the Borat sequel

I was wearing a bulletproof vest, and that’s only the second time in my career that I’ve ever done that. But I was told that there was a chance that somebody might try to shoot at me. I was very aware that once the crowd realized that I was a fake, that it could turn really ugly and it could be really dangerous. …

Sacha Baron Cohen plays a Kazakh TV journalist who travels around the U.S. with his daughter in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm. Cos Aelenei/Amazon Prime Video hide caption

toggle caption

Cos Aelenei/Amazon Prime Video

Sacha Baron Cohen plays a Kazakh TV journalist who travels around the U.S. with his daughter in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm.

Cos Aelenei/Amazon Prime Video

I remember putting on the bulletproof vest before the scene, looking in the mirror of a nearby hotel, and … I remember asking the makeup guy, “Do you think I’m going to get shot today?” And he’s like, “No, no, no, no.” I said, “Well, why am I putting on the bulletproof vest then?” And he didn’t really have an answer.

I kept on coming back to this feeling. Again, I didn’t want to do Borat again. I didn’t want to go undercover again. I felt I had to do anything I could to remind people of what, in 90 minutes, in a humorous way, of what Trump had done the prior four years, and I felt I had to try and infiltrate his inner circle, which we did do with Rudy Giuliani and Mike Pence. We felt we had to do that. I felt I had to get this movie out before the election. But, yes, maybe I’m crazy.

On whether he thinks that there’s an ethical gray area to bringing characters into the world and deceiving people

Those are the discussions that we have in the writers’ room continually: Is this ethical? What’s the purpose of this scene? Is it just to be funny? Is there some satire? Is that satire worth it? When you’re doing stuff like a gun rally and you could get shot, then morally it’s very clear. Or if you’re undermining one of Trump’s inner circle, whose sole aim is to undermine the legitimacy of the election, then, yeah, that’s moral. I mean, look at what Rudy did post Borat coming out. He spread this big lie that Trump had won the election. And that lie is so dangerous and so misleading that it led to the attack on the Capitol — and it hasn’t ended.

So the morality of seeing how Rudy would react when he was alone in a room with an attractive young woman, I think that morality is pretty clear. I think it’s evidence of the misogyny that was trumpeted by the president and was almost a badge of honor with his inner circle. What we did with Rudy was crucial. I mean, we made the movie to have an impact on the election. … So ethically, I can stand by that all day long.

Is the movie as a whole ethical? Yes. We did it because there was a deeply unethical government in power. And there was no question. … We had to do what we could to inspire people to vote and remind people of the immorality of the government prior to the election. … I have no doubt about the morality of this film. I’m very proud of it.

On not appearing as himself publicly to preserve the identity of his characters for many years

I had never wanted to give any interviews as myself. And I had a fantastic period in England where Ali G, which was the first sort of character that I’d done, was a phenomenon in England. Ali G, the character, was huge. It was incredibly famous. … But me, Sacha, I was unknown, and it was just fantastic. I was able to go on the Tube. I was able to have all the benefits of fame and not be famous. So I wanted to continue that, and also it helped my work. I realized that if I became famous as myself, it would make making my work almost impossible. …

I wish I could have carried on like that and not become famous as myself. There are great benefits to fame in that you can speak to people who [you] shouldn’t be able to speak to. People will take your call. … Some people love getting recognized and love the attention. I don’t love it. I loved that period where the shows were really successful but nobody knew who I was.

I remember once, the first time we released the Ali G video — and it was a video back in those days — and I stood in this record store called HMV on Oxford Street, was the biggest one in London, and I was surrounded by Ali G fans who were buying the VHS, and I was dressed as Borat. And they were like, “Get out of the way! Get out! You stink!” And it was such a pleasure for me for them not to know who I was. And then, you know, being on the Tube, the Underground in London, and hearing people talk about Ali G or do Ali G impressions and not realizing that they were next to the man who performed it. For me, that was the most fun period.

On what captivated him about Yippie leader Abbie Hoffman, whom he plays in The Trial of the Chicago 7

He was very aware, of the stage and of the cameras, that he was creating a persona and performing actions in order to get young people motivated. So he knew that he could use humor to, firstly, challenge systemic racism and the establishment. But he also knew that if he was funny and brilliant, which he was, he would be able to get some young people to sacrifice their lives to fight against the Vietnam War. He was influenced by the idea of taking theater into the streets, and he was very, very thoughtful. So he was going on stand-up tours during the trial. They felt very off the cuff; however, they were extremely prepared. He had studied Lenny Bruce — studied the rhythms and also learned some other lessons from Lenny Bruce, including that the trial was a show trial and that they would be convicted. …

“The more I read about him, I did see some similarity [between us],” Sacha Baron Cohen says of Abbie Hoffman, the real-life activist he plays in The Trial of the Chicago 7. Niko Tavernise/Netflix hide caption

toggle caption

Niko Tavernise/Netflix

“The more I read about him, I did see some similarity [between us],” Sacha Baron Cohen says of Abbie Hoffman, the real-life activist he plays in The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Niko Tavernise/Netflix

He was aware that they didn’t have any money — the Yippies didn’t have any money … [and] that he could actually make an impact was by being funny, by doing these seemingly crazy things, like getting thousands of students to try and levitate the Pentagon or nominating a pig to run for leader of the Democratic Party. The more I read about him, I did see some similarity [between us] … to a degree.

On his audition to play Abbie Hoffman (back when Steven Spielberg was attached to direct)

I heard that there was going to be a movie about the Chicago 7. I was kind of obsessed with Abbie Hoffman from the age of 20, and with great chutzpah I called up Steven Spielberg and I said, “Can you let me audition?” And he had some reservations, particularly about the accent, because he knew it was a very specific accent. And he sent me a dialect coach, and … every night we recorded three versions of his speech. And after two weeks, Spielberg said, “OK, I need a version of that speech that you’re happy with. Deliver it to my house at 9 a.m.” So I had recorded about 30 versions. The dialect coach said [to use] Take 28, and I instructed my assistant — I said, “Put Take 28 on a CD. Deliver it to Mr. Spielberg’s house.”

I meet up with Steven … and he sits me down and he says, “Listen, Sacha, I’ve got to be honest. I got the CD. Thank you. The first 10 or so takes were not very good at all.” And I realize my assistant had given the wrong CD. He had listened to all 28. He goes, “By the end, Sacha, it was perfect.” By the way, that is why Spielberg is Spielberg and why a lot of those people are who they are. They’ve got incredible talent, but they sit through to Take 28 when they should have switched off after Take 4.

Lauren Krenzel and Thea Chaloner produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.