The uninitiated see bull riding as the ultimate demonstration of senseless, pointless risk, while the initiated see it pretty much the same way. There’s just no sane reason for attempting to hold with one hand to a creature that has been reduced to pure rage and sinew and hates you with the fire of a thousand suns — unless you think that life is like that already, and there’s nowhere else you can go to be simultaneously trampled into dust and cheered. Nonetheless, the prospect of an inspirational, “Go for It” movie centering on a 14-year-old girl’s attempt to escape her horrible homelife by apprenticing with a mangled ex–bull rider seemed perverse in the extreme — until I saw the film, which isn’t that at all. Annie Silverstein’s Bull doesn’t jerk you around. It doesn’t Go for It. It’s quieter and more pensive than a glib summation (or a trailer) would suggest, but it never goes soft.

The girl, Kris (Amber Havard), has a mother who’s behind bars (and likely to remain so until she controls her temper) and a grandmother who simply hasn’t the energy or stout heart to be a proper surrogate. Kris doesn’t act out in ways that scream delinquent. Her recklessness is strangely detached, as if she’s going with the flow, as if her fate has been predetermined. In a transparent attempt to hold on to her friends, she breaks into the home of her neighbor, Abe (Rob Morgan) — who’s away at the rodeo, being one of those brave fellows who strives to keep bulls from pulping their fallen riders — and parties hard with Abe’s booze, pills, and chickens (which provide hours of indoor fun). Although prepared to go to “juvie” (on some level even wanting to), Kris indentures herself to Abe for a spell that seems to stretch out. She’s in no hurry to stop coming around, and he … well, he puts up with her presence.

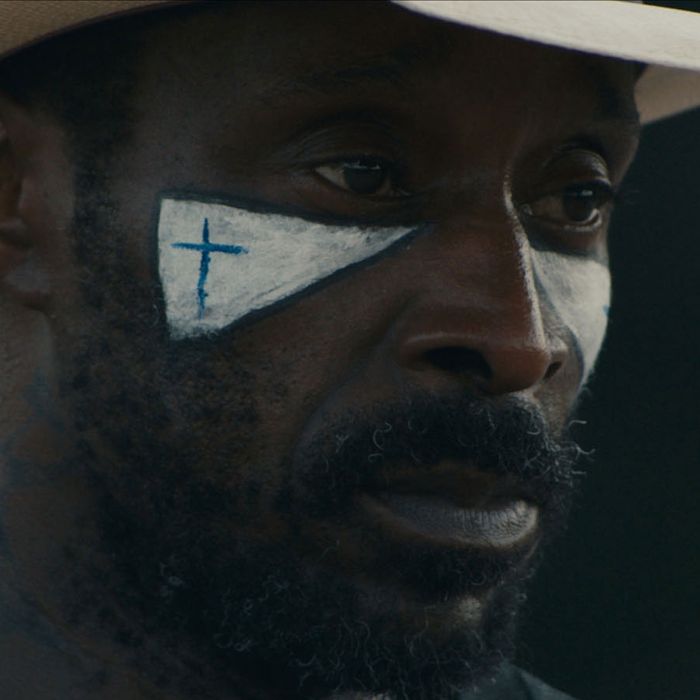

The thing about Abe is that he’s not a lovably crusty old cuss, and if you dread the prospect of him becoming one, relax. He’s withholding on a good day and surly on all the others. There’s a gulf between Abe, who is black, alcoholic, and hardworking, and Kris, whose family is broken and then some. Abe has a self-destructive streak: He seems determined to be run into the ground — literally — and embittered when injuries prevent him from leaving this world with gusto. The good money is in the weekly shows put on by the association of Professional Bull Riders (PBR), but most of his work is now with his local rodeo, which is almost exclusively black. Kris looks even more out of place there than she would at the PBR, but she’s drawn to it. However brutal the goings-on, this rodeo has good vibes, and the black teens who dream of riding the bulls seem in a different universe from the local white kids with their druggie indifference.

A movie like Bull can be appreciated for what it does and also what it doesn’t do. Havard’s Kris is defensive above all. Her nods and headshakes are tiny. She’s not a big talker. But there’s something physically right about the way she sits atop the rodeo’s practice (mechanical) bull. She’s longer waisted than her male counterparts. Her middle is slinkier, more flexible. She looks as if she could someday take the buffeting. I expected from Bull the bovine equivalent of the equine therapy in last year’s The Mustang, in which a wild human and a wild animal find a rhythm and thereby transcend their unhappy selves; but there isn’t the slightest hint here of a mystical transference. Silverstein comes out of the world of experiential documentaries, and her framing (the cinematographer is Shabier Kirchner) — given the milieu — is gentle. Silverstein has an instinct for when to go close and when to stay out of her subjects’ way, when to jangle and when to gaze steadily. There’s little music apart from what comes from the echoey rodeo speakers, and what there is (by William Ryan Fritch) serves as a faintly shimmering counterpoint to the clanging stables, chittering insects, and bull snorts.

Morgan’s performance is beautifully judged. You see his ropiness and where the ropes have frayed and torn. His spirit wants — demands — to charge ahead; his body says, “That’s not happening.” In one scene, Abe is reduced to playing straight man to a rodeo clown and has to steal gulps from a hidden stash of booze to go through with the humiliating spectacle — until he gets ripped and starts to get all Lenny Bruce and has to be dragged out of the ring. I was thinking that a dyspeptic rodeo emcee would be a good job for him, but it would also be an express train to alcoholism. Meanwhile, at the point in Bull where we expect Kris to be busy acclimating herself to the bulls, she is suddenly selling drugs for her mother’s creepy ex. A scene in which she lures a now-clean rider into springing for Oxycontin is heartbreaking, not just because Kris has fallen but because she’s so talented at bringing others down too.

Bull doesn’t underscore anything, and, as a result, you never get the good-hygiene girl-coming-of-age-on-a-farm vibe that became a cliché of Sundance-developed movies in the institute’s early days. (Sundance — which provided support for Silverstein — has learned that lesson well.) The film isn’t a sensory feast like The Rider or as packed with high drama as The Mustang, but in some ways I prefer it. It’s a stoic work, but its stoicism looks, in the end, like mercy. The filmmaker doesn’t intrude because that would seem like colluding with the Fates, and the Fates are spurious, constricting, anti-life. Neither Kris nor Abe knows what should come next, but they know what shouldn’t, which is a beginning.