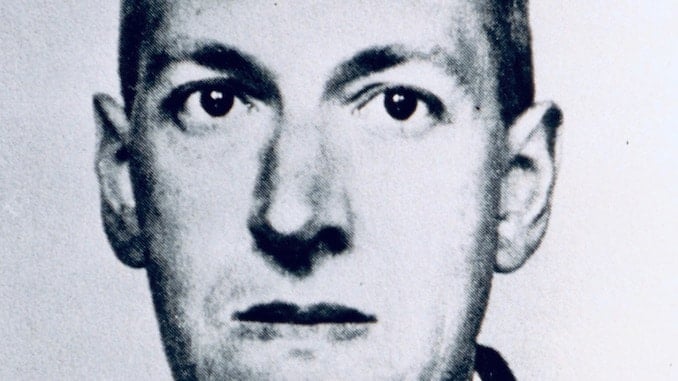

HP Lovecraft was a racist, an antisemite, and a white supremacist. And it’s time for Rhode Island to deal with those exclusive facts about the influential author that the state tirelessly lionizes.

Celebrated with walking tours, film festivals, a convention, and a bust in the Providence Athenaeum – which also devotes a sanitized page to the author on its website – HP Lovecraft is Providence and Rhode Island’s darling literary son (in a short field). In his work, he elevated the anxieties of a changing age into a vast and terrifying mythos. His themes and techniques were startling in their novelty and influenced many of the best-regarded and most successful horror, fantasy, and science-fiction writers of our time. His achievements, if they could stand away from their author, are significant culturally and literarily. But those achievements can’t stand away from their author. Their author was a racist, nationalist, and antisemite with a long paper trail and those achievements are everywhere found to be informed by the author’s bigotry, fear, and hate.

This poem is among the better-known examples of Lovecraft’s racism, but it is only superficially known: readers of this essay are encouraged to navigate to and make their own judgment about its virulence and intent. It was written by Lovecraft in 1912. And it was not peculiar for him. In countless letters he railed against African-Americans, immigrants, Jews, and other minority groups. “…The Negro is fundamentally the biological inferior of all White and even Mongolian races,” one such letter says. In another letter, Lovecraft described the discomfort of having to live among varying races in New York City:

“The organic things—Italo-Semitico-Mongoloid—inhabiting that awful cesspool could not by any stretch of the imagination be call’d human. They were monstrous and nebulous adumbrations of the pithecanthropoid and amoebal; vaguley moulded from some stinking viscous slime of earth’s corruption, and slithering and oozing in and on the filthy streets or in and out of windows and doorways in a fashion suggestive of nothing but infesting worms or deep-sea unnameabilities.”

That should evoke his fiction – and draw the clear line between it and his racism – without the aid of the writer of this essay. But that very horror he transposed directly into his fiction, no veils, no metaphors, no parables. “The Horror at Red Hook” eschews the fantastic beasts and monsters that seem to stand in for non-whites and immigrants in favor of those people themselves. The “horror” at Red Hook, it is discovered, are the “Syrians, Spanish, Italians, and Negros” of Red Hook, Brooklyn, where Lovecraft regretted to reside for a time. These teeming hordes of monsters with their “half-ape savagery” besiege the world but for the might of the standing Aryan culture.

Living in Red Hook was, for Lovecraft, like being “imprisoned in a nightmare.”

According to his wife, Sonia Greene:

“…Whenever he would meet crowds of people – in the subway, or at the noon hours, at the sidewalks of Broadway or crowds… These were usually the workers of minority races – he would become livid with anger and rage.”

Integration was a primary horror for Lovecraft. “…Anything is better than the mongrelisation which would mean the hopeless deterioration of a great nation,” he said. And nothing but “pain and disaster will come from the mingling of black and white.”

A later work, the poem “Providence in 2000 AD,” Lovecraft imagined the displacement of the white race by immigrants. The parallels should be clear: The protagonists of Lovecraft’s stories discover and confront repellent and conquering beasts that are stand-ins for the different races encountered by Lovecraft in the real world. The beasts, marvelous as they are, are constructions; the displacement, to his racist mind, is not. Lovecraft had the same nightmares during his waking hours among immigrants, African-Americans, and Jews.

In his antisemitic conspiracy theories, Jews wielded the New York aristocracy as a weapon against the Aryan race. He insisted “the Jew must be muzzled” before he could “degrade and Orientalize the robust Aryan civilization.” He sympathized with the “romantic and immature” worldview of fascists and nationalists. “I know he’s a clown, but God I like the boy,” he said of Adolf Hitler. Lovecraft’s antisemitism was so transparent and virulent that his Jewish wife felt compelled to confront him. He capitulated: She “no longer belonged to those mongrels,” he said.

His lack of sympathy for minorities extended beyond those under siege in Eastern Europe. He considered lynch mobs in the American south to be “…Resorting to extra-legal measures such as lynching and intimidation because the legal machinery does not sufficiently protect them.”

These are not the views of a man poisoned by the drink of the times. Lovecraft’s bigotry confounded many close to him, drew him into violent debates, and alienated him from literary circles. Nor are these examples like others: the curious antisemitism of Henry Miller, the fascism of Ezra Pound; Arlo Guthrie saying “fags” in “Alice’s Restaurant;” Lenny Bruce saying “are there any niggers here tonight?” Nor are those figures – excepting occasionally the Newport-connected Guthrie – honored so publicly in Rhode Island.

The World Fantasy Award has replaced the likeness of Lovecraft it used to honor its recipients, for the reasons above. It’s time for Rhode Island to follow suit and cease the endless honors bestowed upon this hateful and bigoted man whose character cannot be separated from his work. At the very least, the occasions and places with which we honor him should be utilized to also educate the observer with the truth of his character, that they might decide where the man ends and the work begins, and whether the latter reconciles the hideousness of the former. It should be decided that it does not.